2. Construction

Entering a New Dimension

It takes an average of nine months for hired contractors to build a house, the Census Bureau’s 2017 Survey of Construction says. Against this backdrop, one can see the appeal of a faster mode of residential building.

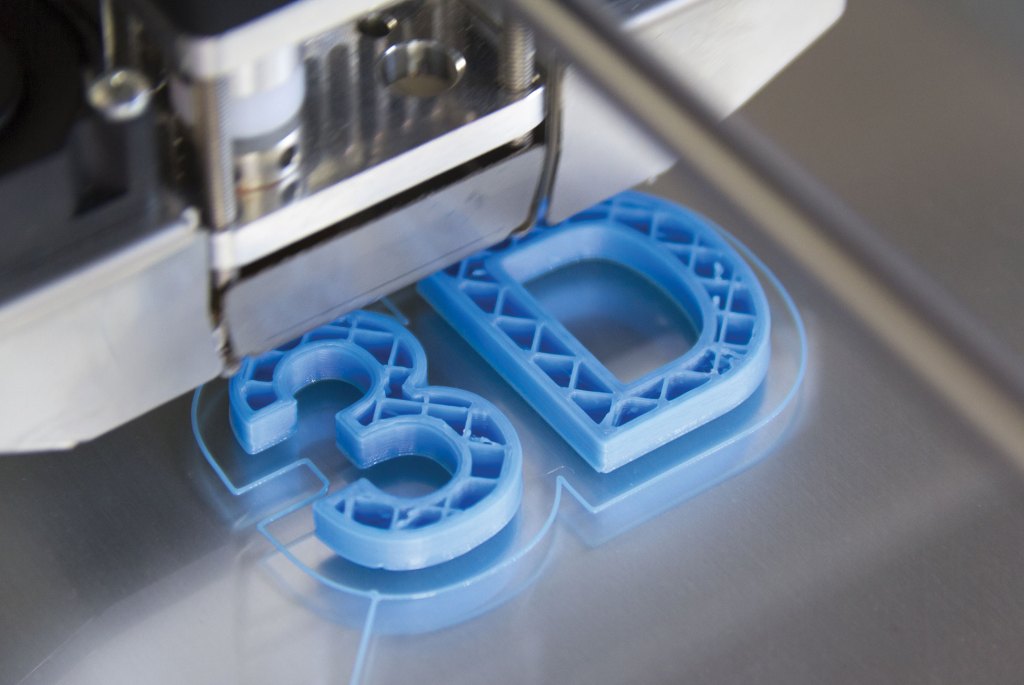

Enter additive manufacturing, also known as 3-D printing. Since 2014, companies in China, France, and even the United States have printed 3-D homes in fewer than three days. Theoretically, the widespread adoption of concrete-based additive manufacturing could spell bad news for lumberyards. As things now stand, though, there’s a large disconnect between what researchers say additive manufacturing can do in residential construction and the current reality.

“Additive manufacturing is a long putt,” says Ashwin Himat, director of growth and innovation at LP Corp. “I’ve seen plenty of one-offs but nothing beyond that.” Technologies, material ratios, and techniques need to be tested and refined before additive manufacturing is ready to disrupt the traditional methods of residential construction. It will likely be decades before 3-D printing takes off in residential construction, if at all.

Behrokh Khoshnevis, CEO and president of building printing technology firm Contour Crafting Corp. and a professor at the University of Southern California, says the widespread development of additive manufacturing depends on researchers’ ability to provide tangible proof of its economic advantages.

So far, there hasn’t been much evidence of that. Khoshnevis says most 3-D printing of buildings involves only the shell, which accounts for just 30% of the cost of construction. Building-code regulations and the durability of structures also are preventing 3-D printing from asserting itself as a major player in residential construction.

What 3-D buildings will be made out of is another question. Concrete, recycled materials, and chemical compounds are among the popular materials being experimented with in additive manufacturing. Some of the materials, while environmentally friendly, are incompatible with large-scale residential construction projects.

One of the most abundant and popular materials is sulfur concrete, which consists of sulfur and aggregate but not cement or water. Sulfur concrete can melt at high temperatures, making it unsuitable for home construction.

Meanwhile, research on how to include wood fiber in 3-D printing is going on at several sites in the U.S. and Europe. The University of Maine is installing a huge 3-D printer to test 3-D building materials made of a composite of wood fiber and plastics—the same key ingredients in composite decking.

Khoshnevis says that while 3-D printing could be a disruptor to lumberyards if it’s widely adopted, one must remember that competition between materials such as concrete, steel, brick, and wood already exists. The addition of 3-D printing would only bring another player to the table.

A realistic time line for 3-D printing in residential construction is hazy. The most ambitious estimates are that it will take another 10 to 15 years for scientists to fine-tune the printing systems, material durability, and ratios of materials. And even then, developing the technology available for 3-D printing is no guarantee that the conservative construction industry will adopt a radically new production process.

Goodbye to the Garage?

It can take decades for master-planned projects to get approved, so developers have to build based on not just what’s popular today but what’s likely to be popular years from now. To help them choose the right trends, they often turn to Metrostudy chief economist Mark Boud. What’s in his crystal ball?

Boud sees a time when suburban homes will include smaller garages or stop including garages altogether. That’s because people will be riding in self-driving electric vehicles instead, and after the car drops off a home’s occupant at the front door, the vehicle will toddle off to a central facility, where it will plug itself into a charger and maybe text the facility’s sole human being that it needs an oil change.

Mass Movement

The line between residential and commercial construction in America looks likely to get much fuzzier in the coming decades.

This winter, the International Code Council (ICC) could consider changing the International Residential Code in ways that would permit using wood to build structures six to 18 stories high. For proponents who make or use what’s known as mass timber, a win would open the gates to a big new source of business. For lumberyards, victory could fundamentally change what they stock and who they sell to.

“The advent of new technology like mass timber is our entryway into nonresidential markets,” says Robert Glowinski, president of the American Wood Council, a trade group for wood products firms. “I think we’re at 88% to 90% [penetration] of the residential construction market, but in nonresidential we’re at 12% to 14%.”

Bill Parsons, vice president of operations for WoodWorks, the chief advocacy group for mass timber, figures there is 200 million square feet of annual construction opportunity for mass timber if the ICC votes to change the rules. He also sees potential in low-rise commercial structures that today are “built by people who don’t think about wood.”

Mass timber generally refers to wood products created out of multiple layers of wood and used to support a lot of weight. One example is cross-laminated timbers (CLTs), in which solid-sawn wood is glued side by side and then glue-stacked in alternating directions.

Mass timber has been used in Europe for years, and a few examples have been erected in North America in communities that have permitted exceptions to local building codes. That’s why the ICC is so important, says John Klein, a research scientist at MIT’s architecture department and a principal at John Klein Design. “Once developers hear the word ‘variance,’ that means time, money, and lawyers” that they’d rather avoid, he says.

A favorable ICC vote could persuade big companies to get involved. It takes time and money to build a mill that can turn logs into CLTs, laminated veneer lumber, or similar products, and to date none of the major timber companies has made that commitment.

“We support it, though we’re not in the CLT game,” says Chris Reiten, national business development manager at Boise Cascade. “The opportunity is fairly narrow [right now].”

Georgia-Pacific senior marketing manager Jeff Key says his company isn’t investing in mass timber today but adds: “I wouldn’t be surprised to see it as a widely accepted practice in the next 30 years.”

“Conversations are happening,” Klein says. “We don’t have the infrastructure. But in 30 years, [activity] will dramatically increase.”

-

5 for the Future: Demographics

Projections on how the demographics on the U.S. will change over the next 30 years and what retiring millennials will mean for the residential construction sector.

-

5 for the Future: Environment

Future natural disasters will put a greater emphasis on resilience; building material suppliers could be contributing to community sickness; what rising water levels mean in the future.

-

5 for the Future: Logistics/Products

The future of manufactured homes, trucking and rail transportation, clothing fabric materials, and microscopic building materials are explored.

-

5 for the Future: Technology

Big data likely has a big role to play in LBM in the future and blockchain has the potential to revolutionize tracking and verification.

-

5 for the Future

The key trends that will shape construction and LBM through 2048.