1% Unemployment

It’s fair to say that the lumberyards in the Bakken area are grateful for the prosperity that the oil fields have brought—with reservations.

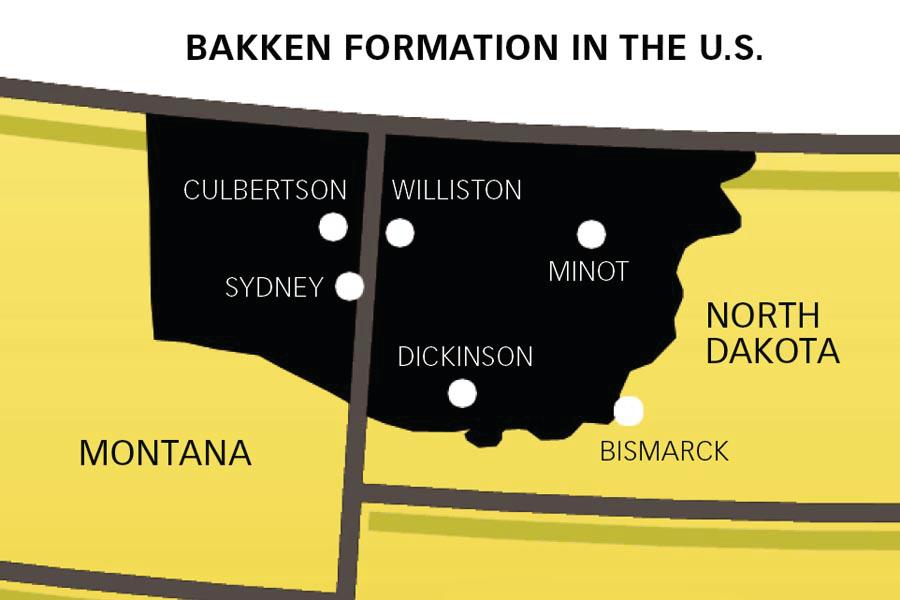

Dealers like Western Building Center want in on the action, says Shanks, because the economy in his section of Montana, on the western side of the continental divide, is sluggish, with an unemployment rate over 10%. In Williston and surrounding Williams County, the unemployment rate is less than 1%. “A while ago, rumor had it that a big-box store was going to open up in Williston,” says Bosch. “They had 300 jobs to fill and held a job fair; only 30 people showed up. So far, no big box has opened.”

Like most lumberyards in the Bakken formation, Bosch supplies building materials only—no specialty items for the oil field fields. Energy companies have their own suppliers for that, Troy says. While he’s certainly picked up business from the oil boom, mainly in supplying both local contractors and out-of-state builders putting up residences, hotels or temporary worker housing, of the out-of state contractors, he says: “You can’t get too excited if you only get paid on 20% of it.” That can easily happen if a non-local gets overextended and goes out of business.

For Troy Bosch, a real downside to the current boom is the employee situation. “We’ve had to pay more. I have to compete, or else I see a truck from Minnesota coming here.”

One of those trucks might have been hauling in factory-built cottages from Hilltop Lumber in Alexandria, Minn., destined for worker housing in Williston as well as 75 miles east in Stanley. “We’ve brought in 110 of them,” says Brian Klimek, Hilltop general manager and vice president. Hilltop has also trucked in building materials for the man camps, working with a local contractor who had a contract with Target Logistics to build the temporary worker housing.

Changes in Dickinson’s quality of life also make Troy uneasy.

“My wife works at the hospital, and we hear the stories about domestic violence increasing, and in the schools we hear about kids having to keep the households going because both parents are working,” he says. “Everybody in Dickinson locks their doors now. Prosperity is not all about the money.”

‘It’s the Badlands’

Crane Johnson Lumber is one of the luckier dealers. The dealer’s’ board had been looking over the situation in the western part of the state for a while now, considering its options. “As much drilling as they have been doing, there is a huge amount left to go,” says company president Briggs.

Experts estimate Bakken Shale has anywhere from 10 to 35 years of drilling left. Bakken’s rich reserves, the dealer’s ability to purchase a suitable piece of land, and the availability of staff willing to move west led Crane Johnson to take the plunge. The dealer bought a 12-acre parcel of land in Surrey, a small town 8 miles east of Minot, back in January.

“The environment is so different—as you go west of Minot, it’s wild, it’s the badlands out there,” Briggs says. Wild or no, Crane Johnson has decided to throw a saddle on that bronc and settle down for the ride. “Now we can take advantage of what’s going on, and get a little share of this [oil money],” he says. The Surrey location is slated to open this fall.

Well aware of the housing problem attendant on opening a lumberyard in the Bakken area, Montana’s Western Building Center is planning to construct two houses on the same parcel as its new yard—a 10-acre parcel in Culbertson, Mont., right on Highway 2, just under 50 miles from Williston. “This past year we have sent a lot of building materials to Williston,” says WBC’s Shanks. “I guess we’re going to roll the dice. Our goal is to be up and operating in July.

“The day we open the door, we’ll have five people plus possibly a part-time bookkeeper. We’re hoping by the first month to be able to double that number.”

Losing employees to the oil fields is not uncommon for lumberyards within range of Bakken, a consequence of a world in which one can earn $100,000 a year just driving water trucks. Dealers have had to follow suit and pay higher wages to retain their own employees as well as attract new ones.

Minot’s Muus Lumber & Hardware has also lost employees to the oil fields. “Nobody can compete with them,” yard manager Heidrich says. Like Bosch in Dickinson, Heidrich has also noticed an increase in crime, “More robberies, murders and rapes, and domestic violence is way up. You lose that small-town feel.”

Meanwhile, Schaefer is considering the future.

He has read that it takes three million to four million gallons of water to drill a well, and the state has 200 rigs currently drilling (in production, North Dakota trails only Texas) with leases for more wells being negotiated.

“Where does all that water go?” Schaefer asks. “I’m not exactly sure. It doesn’t all stay in the ground. It’s one of those double-edged swords. Do we really know all the full effects?

“The business is good, we can’t complain about that, but I hope that the drilling doesn’t have a negative effect on the land and the people.”